This Paradox disproves Free Will (Yes, even compatibilism)

Free Will is ultimately an illusion that people just so happen to believe is real. Because most of us collectively agree that we feel like we have it, we structure everything we do around it. But even this sentence disproves free will. We tend to feel like we should have free will intuitively, and due to that feeling, we act as if we do, not because we’re choosing in some causa sui (original and without preceding cause) manner. The thing is, feelings alone don’t justify anything. Someone may feel they are God, and you may indulge them. But at the end of the day, that alone doesn’t make them God or anything else other than a human with a god complex. If you can put a reason for it or ask a “why” about it, it’s not free. I’m confident that by the end of this blog post, you’ll agree beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Folly of Free Will

So, right off the bat, we need to clarify what I mean by free will (Source: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). However, I want to point out that that itself is one of the problems. There’s no uniform consensus on what it even means. Unlike gravity, which has a single meaning that can’t be misconstrued when referring to the force that weighs us down, the concept of free will means vastly different things to different people who have a vested interest in saying theirs is the true definition. A religious person's definition may sound vastly different than a political person's, and the subject of queerness is enough to prove it. Most people have certain things they like to exclude as being outside of their control, from neurodivergence to their addictions. So, it’s often considered “radical” when I weigh in that there is no such thing as free will at all.

“No matter how you define Free Will, it’s wrong”

Free will is what I call a “Primeval Shackle” or a primitive concept that has served some purpose but is not advanced nor useful enough to help push humanity forward. These beliefs shackle us to our basest tendencies, encourage unfounded superstitions, and prevent us from the path to achieving societal and individual enlightenment. Up to this point, I haven’t been too clear about my philosophical stance on this blog. A part of my work as a philosopher is identifying and providing the tools to unshackle ourselves from these chains we are biologically programmed to live in. These shackles include free will, superstition, wisdom, and even hope. I’ll go into more detail on these later, but the point is that despite most of them sounding positive, these beliefs are a double-edged sword and are quite outdated. Of all these, though, the concept of free will has plagued humanity since its inception.

A Prediction

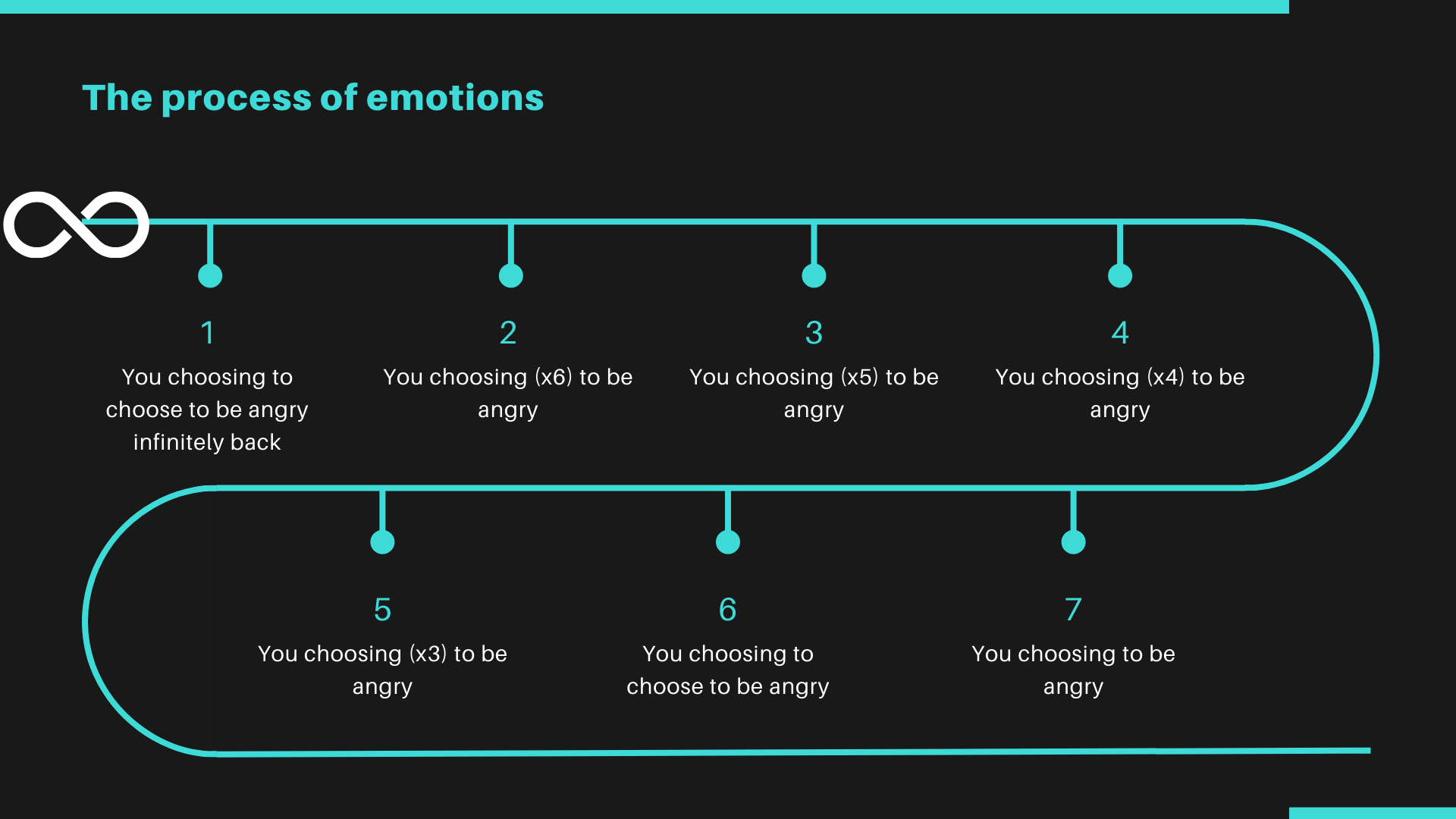

Allow me to make a prediction. Some of you, perhaps even most, may react to my assertions with anger. But let’s even take a look at that. This anger is clearly reflexive, as it seems odd that you or anyone else would choose to be angry. Anger doesn’t exactly feel the greatest, and studies show that usually, it’s not too great for our health. Yet why are so many people angry and miserable? It’s akin to inflicting a kind of mental self-harm, yet we look at physical self-harm as purely active. To say someone chooses to be angry is itself a paradox, as in order to choose to be angry, the position you make that choice in would necessarily have its own emotional state, even if it’s neutral. Let’s say that you were happy before reading this article. Well, then, you’d be happily choosing to be angry or choosing anger from a standpoint of happiness. Essentially, wherever you are, you come from somewhere. But then, wouldn’t that make you ultimately happy? When you see a movie, you have to suspend disbelief because it’s clearly Jake Gyllenhaal playing the main character in the movie Road House. He’s part of the appeal, and that’s why it’s got his name and face on it. It’s a production. Jake is acting as the protagonist, and we’re not just recording an actual circumstance. In the same way, if he had a bad day on set in real life, he had to have acted a certain way for the sake of the movie, regardless of his actual anger. I say all this to say that it wouldn’t look like this if we actually had control over our emotions. We are reacting to sensations and stimuli that happen to us. To say we choose anything leads to a situation called an infinite regress when taken to its logical conclusion. For example, someone might disagree that we choose one emotional state from another despite the fact that this is clearly demonstrable. (You don’t ask your boss for a raise when he’s angry at the office. You ask him when he’s in a good mood. If after you ask, he shifts from a good mood to an angry one because he doesn’t like you asking, it’s not because he’s choosing to be angry over the topic; it’s because the topic brings anger out of him, for one reason or another but he didn’t choose to be greedy or whatever other reason he’s acting that way.) Now, when it comes to infinite regressions, they can occur for a number of reasons. An infinite regress (Source: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) is a pattern in which no discernable beginning can be traced within a set of something. In this case, it occurs when someone assumes they can choose their emotions.

“Do you create your personality from the ground up, or do you just wake up one day around the age of four as yourself?”

You’d have to be in a state that contained its own emotions to pick your emotions, but in this predicament, there’s no beginning state one could choose from which this all stems. Think about it. Do you create your personality from the ground up, or do you just wake up one day around the age of four as yourself? If your response is that you created your personality first, of all… no, you didn’t. Secondly, what state were you in to be able to do this? What preferences did you have? Well, we run into the same problem infinitely back. If you chose even that, you were in a state where you chose that too, and so on forever. It would never discernably begin or end. This means that something within you is just shoving you in a direction. This is one of the many paradoxes that arise when people try to claim free will of any degree.

What it looks like if you say you choose your emotions

At some point in the image above, you have to realize that, no, you didn’t choose. It’s just happening to you. Especially when, again, at each junction where you make the decision, you would be in your own state, having your own emotions. This is utterly unreasonable and overlooks the fact that emotions are just something that happen TO you. You get no choice. (for those who think, “Yeah, but I can decide how I respond to them.” I want you to read my paradox, then try saying that.”) Even compatibilism (also sometimes known as compatibility between moral responsibility and determinism) tries to say that even though we have no control over the personalities we were born with, it’s ultimately still up to us to control that which we didn’t create. This makes no sense, though, because if we’re not born with the innate capacity to do these things or are even aware of them, how could it possibly be fair or moral to state that it’s our job to develop these things? It’s like asking someone who has no prior training in martial arts and is, in fact, disabled in some way to become a master. Even if we say, “Well, they can do this over the course of their life.” They’d have to have the potential, opportunity, financial, personal, responsibility, willpower, athleticism, etc., to achieve any of this to the slightest degree. If we could choose, we’d have chosen the maximum percentage of all these things. Yet, as you can see, we clearly don’t possess the ability. Compatibilism attempts to say that we have the ability to determine and control our own internal landscape regardless of external circumstances. You know. The one we get born into? As I’ve said, this distinction is arbitrary, as you can see in this example of martial arts. And not just that. I wonder if you’ve noticed it, too what I did back there with the process of emotions. See, if emotions come from within you, but you don’t pick them, then I’m confused about how compatibilism can be valid or coherent. You see, the emotion you just had was internal. Yet your desire to resist it was also internal, was it not? So we’re dealing with a double internal. Compatiblism’s differentiation between internal and external influences simply doesn’t hold here. You’re being caught between two internals. Your emotions that you don’t pick, and your desire to control them, which ironically enough, you still can’t control not having. It’s why meditation is explicitly structured to do the opposite. To get you to stop your innate (not freely willed) desire to control.

The Paradox I’ve Been Talking About

Hopefully, I’ve made my point so far. If this has made you at least think about things, that would be great, but there’s so much more to say. I loosely showed you a paradox regarding emotions and how we don’t control them. The paradox that I titled this article after isn’t that one. I’ve never seen anyone solve this paradox that I’ve discovered, and it’s the one that I’m confident totally disproves the concept of free will. It goes like this.

“Thought paradox: Thinking doesn't give you free will because we don't control the output of our thoughts. If we did, we'd have cured cancer and made flying cars by now. We'd be able to solve any math problem on command. The output is the result of a process. You may think to want to have a business idea that will make you a billionaire, but that doesn’t automatically lead you to have one. You don’t even have control of where the thought will ultimately end up. You may want to do homework but can’t stop thinking about a great movie you saw. That output is clearly irrelevant to the input. You also don't control the input (intelligence, what you're putting into the thought process like emotions and prior thoughts, depth of deliberation, how long it will take to complete) of your thoughts especially (and I can’t state this enough) if the input is the output of another thought which it always is. Everything is predetermined by the output, which again is outside of your control. If you like the output, you'll likely try to act on it. But how do you know you'll like it? You'd presumably have to think about why you do because if you don't, it'd be thoughtless and therefore not willed in the sense that free will tends to suggest. This is also before you factor in that the input of any thought process is always the output of other, prior thought processes. You either are going to act in accordance with the thought or not. And this makes even less sense when you realize that you can like the output but not do anything with it (like me with ADHD wanting to clean my room but not doing it) or hate the output but feel compelled to do it (like someone struggling with addiction). There's no control there. But even still, just to be extra fair, let's cut out those parts and reduce it to just when you actually like and do/dislike and don't do the output. You're still not free because unless you think about why you like or dislike the output, then you're mindlessly liking it or disliking it, which isn’t free in any sense of the word. All you can do is delude yourself into thinking that you’re free within your prison cell. And if you do put thought into it, you run into the beginning of this paradox again infinitely many times. So, as I’ve shown, you can’t control the input or the output, nor can you control the process that leads you from the input to the output. If you were to try and do that, you’d have to think about it, which once again runs you into the beginning of this paradox. Anything you can presuppose about how to deal with this thought either involves thinking, which runs into the beginning of this paradox again, or not thinking, which I don’t even see how you could begin to argue, is indicative of any kind of conscious choice. It’s literally mindless. To top it all off, the lines we would use to draw the difference between the output of one thought process and the input of another are mostly arbitrary. In some sense, thoughts are always changing and evolving, so the process is never completed. Rather, you are consistently reacting to forces that seem to arise in your mind and outside of it, but even then, those forces are arbitrarily differentiated. Regardless of what compatibilism might say. If something was advertised to you, but you ignored the advertisement only to have a craving for the product later, can we now say this is an internal thing even though it was planted from the outside? By that logic, anything you happen to hear, see, or experience is an internal thing, so why even make the distinction? You may be wondering what this means for you, and the best way I can explain it is that you are an infinite progression of selves watching a movie of the self directly in front of you and unaware of the selves that are watching you from behind.”

An illustration of the thought paradox

This paradox is an excerpt from a book I’m writing on the subject. My working title is “50+ Paradoxes of Free Will”; if you think these paradoxes are something, just wait. I have more than 70 of them that I’ve discovered (Yes, I actually have so many that I had to narrow down what I’m including in the book) to the point that by the end of the book, I’m confident that the concept will have no room left to stand on. Some of you may ask, “How does this definitively disprove free will?” Well, let me ask you, given the paradox, at what point do you come in to make ANY decision? Wait before you answer; please realize that you’ll either have to think or say it mindlessly and there you go. This isn’t a matter of the concept of free will having limitations. It’s a matter of it being utterly non-existent. At no point in either of the paradoxes I’ve shown can someone decide “THIS. This is where my power lies.” Without it being totally arbitrary. You may wonder what the implications of this are, but let me just say they’re huge. Everything changes with this realization, from religious to political to economic, legal, and philosophical. That’s why I said in the beginning that each of these groups uses different “versions” of the concept to suit their needs. The religious person will tell you that you “chose” to sin despite telling you that you have “original sin” that compels you to sin (make it make sense.) The political person will tell you that you chose to be on the other side of whatever culture war they’re in right now despite the fact that these things are shown to be largely stemming from cultural exposure and psychological predispositions (again, make it make sense.) The economic person will tell you that you chose to buy the things that have been marketed to you despite the fact that they spend billions learning exactly how to use psychology to get you addicted to their products. (How can the field of psychology even exist if people have free will? Isn’t it strange that even though we’re supposedly free, we tend to do the same things over and over again, to the point that they can be deterministically studied? This wouldn’t exist if we had free will.)

Thank you so much for reading this article. I’m an original philosopher who studies these subjects unclouded by the Einstellung effect (Source: Cognition Today) that those in the confines of academia may not. Due to that, I don’t tend to refer to other philosophers. I typically research my own material without referring to Hume, Descartes, or whoever they discuss in the ivory tower. And the proof is in the pudding. You will likely see that nobody else has ever discovered this and my other paradoxes. (Although, to be fair, I wouldn’t know if they did.) If it wasn’t made clear in my about me section, I’m disillusioned with academic philosophy and its tendency to forgo the search for actual answers so that it may self-referentially navel-gaze. But that’s another rant for another day.

If you learned something from this article, then feel free to stick around. The implications that need to be discussed on this subject are nigh-endless. I’ll be writing more articles on this subject as time passes, but please message me if you have questions or comments. If you enjoyed this, please consider funding my blog and book’s publication or subscribing to the newsletter when it’s up. On my Ko-Fi account, I’ll post extended discussions on articles like this one and address some counterarguments. With enough help, I’ll be able to buy a good microphone to record with as well as get other kinks smoothed out. But at the end of the day, you really have no choice. I either made such a convincing argument to you, or you were in the right frame of mind to grasp what I was saying, or I didn’t, and you aren’t. We don’t have any choice or control over these things.